George Westinghouse was a titan of American industry. Like Bill Gates, he made a fortune by controlling a vital standard. He also lost a large one by overextending himself.

Before Bill Gates, there was …. George Westinghouse. Westinghouse was as much a titan of American industry in his day – the latter part of the nineteenth century – as Gates is now. And, like Microsoft, Westinghouse Brake and Signal controlled one limited, but central component of the new infrastructure. Almost all railroad cars and trucks then used Westinghouse brakes, as almost all personal computers today use Microsoft’s operating system. And both men made a fortune from the market position they established.

A train is made up of many coupled carriages or trucks. Safe operation requires that all these components can be stopped by a single system controlled from the locomotive. As railroads expanded, the need for such a system became imperative. There were several available. One of them was Westinghouse’s compressed air braking system.

Whatever method you adopt, you need to apply it to all the trucks or carriages in the train. In practice, if you are to use your rolling stock efficiently, each company should fit the same system to all its vehicles. And if rolling stock was to move freely between the networks of different corporations, all companies needed to adhere to the same standard. Compatibility didn’t matter so much for passenger transport, where firms mostly operated their own trains on their own track. But it mattered a great deal for freight, where you hoped to be able to ship a truck from one side of the United States to the other without unloading and reloading it along the way.

The position of the Burlington railroad became critical. Burlington, which operated lines out of Chicago, was important in its own right. The opening up of the prairies had been one of the great achievements of the railway age. But Burlington was also the gateway between the eastern and western states. Once Westinghouse had persuaded Burlington to adopt his air brake system, success was assured. After a series of demonstrations throughout the United States, Westinghouse air brakes were adopted almost universally. Vacuum brakes – which some thought superior – lost the standards war.

IBM was to Bill Gates what the Burlington railroad was to Westinghouse. IBM’s sponsorship of MS-DOS promoted it as effectively in the personal computer world as Burlington’s adoption of the Westinghouse system did in the American railroad industry. The copyrights that protect the Microsoft operating system correspond to the coupling patents that enabled Westinghouse to defend his system against imitators. Vacuum braking was the nineteenth-century analogue of the Apple Mac. Its followers were passionate devotees, but they were inevitably a shrinking minority.

The Westinghouse and Microsoft cases are unusual events in business history. Both markets were bound to produce a dominant standard because of the need for compatibility. All American railroads wanted compatible rolling stock. All personal computer users want the operating system for which the most software is written. The winners happened to be Westinghouse brake and MS-DOS. It didn’t have to be them, but if central braking systems and personal computing were to take off someone would inevitably achieve market dominance..

There are compatibility standards in many markets. Many standards are common property – the 4’8½” railroad gauge was an even more important compatibility standard than the common braking system, but the spacing of the rails was not something anyone could own. Some standards are determined by government regulation – such as the size and number of lines on a television picture. Most proprietary standards are freely licensed, and successful only because they are. VHS beat Sony’s Betamax video recorder, and Visa credit cards are more widely used than Amex, because JVC and Visa encourage other users whereas Sony and American Express sought to maintain control of the standard for themselves.

The nearly unique achievement of first George Westinghouse and then Bill Gates was to establish a universal standard while maintaining tight proprietary control. For each of them, the result was not only a huge personal fortune, but the opportunity to create a firm which provided a platform for expansion into other markets. But that expansion carried risks and dangers.

Building a market position around a standard is possible only very rarely. Westinghouse hoped to replicate his success with brakes by achieving dominance in the supply of signalling equipment to US railroads. He failed. Signals are fundamentally different from brakes. There are standards in signals, of course – it really does matter that everyone knows that red means stop and green means go and that there aren’t places where it is the other way round. But no-one owns, or can own, that standard.

There is no need for a common standard in signal operation. You could use different designs of signal along the same line, and railroads did. They were free to pick the best signal. Or what their engineers, an idiosyncratic lot, thought was the best signal. It was not like brakes, where you were forced to choose the one that everyone else had chosen.

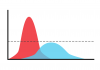

And that poses an issue for Bill Gates, or anyone else planning to invest in the next generation of information technology. Are you selling a brake, or a signal? For brakes compatibility is more important than excellence, and market dominance is inevitable – not necessarily for the best product, but for the product that captures IBM or the Burlington railroad. For signals your own assessment of product quality guides your decision, and it matters little whether or not others have made the same decision. In the market for brakes, any common standards will be firmly entrenched. In a market for signals, a better product can quickly displace an established one.

There are a few brakes in the new world. But there are more signals. So be sure to know which you are dealing with. George Westinghouse ultimately overstretched himself and lost control of the empire he had built.