As every reader of a tabloid newspaper knows, the EU has been interfering with our jam:

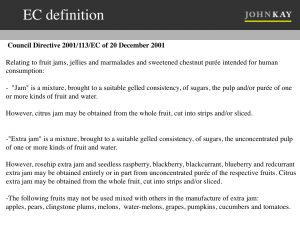

There is an EU jam regulation. In fact, there is an EU jam directive. Here is an extract:

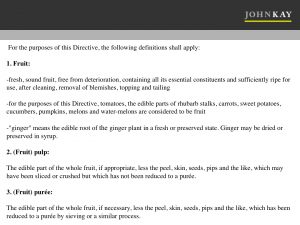

Now EU directives have to be translated into domestic regulations. The following regulation has been in place since 2004.

At this point, you may be checking to see that your UKIP subscription is up to date.

But stand back a moment. What is the purpose of this regulation?

All developed countries have extensive regulation of their food and drink industries. If you buy a jar of jam, you want to be confident it is not poisonous: you want to ensure that it resembles what you expect when you hear the word ‘jam’. Libertarians might dispute the necessity of such regulation: Are not the civil and criminal law, and the concern of suppliers for their reputation, sufficient to protect us from toxic or inferior jam? But history suggests that the answer is probably no. Britain’s Food Standards Agency came into being after ‘mad cow disease’ transmitted through the food chain, having infected several hundred people with a terminal degenerative illness. In any event, there is no advanced country in which such libertarian arguments have been found persuasive.

But when countries determine their food regulations independently, they will come up with different answers. Often for essentially arbitrary reasons: Asked to define ‘jam’, it is probable that French civil servants will come up with somewhat different answers from those reached by British civil servants. And different countries will have different jam-making traditions, and their jam makers may have chosen different areas of specialisation. Their lobbying will influence, perhaps determine, the local jam regulation.

Free trade in jam, or any other product, requires some measure of coordination, a move towards a broadly common perception of what is ‘jam’, to avoid necessity or opportunity for opening jars of imported jam to see what is in them. This coordination is the process of removing non-tariff barriers to trade. The European Union’s single market is the result of such coordination. Not just for jam, but for thousands and thousands of products.

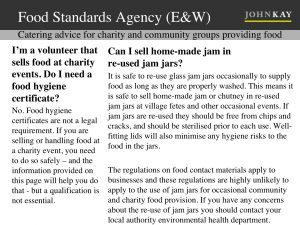

The EU does not have a jam directive because some power-crazed bureaucrat in Brussels wants to interfere with the sale of jam at the village fete. If silly disputes over food standards do arise at village fetes – and they sometimes do – it is because an over-zealous trading standards officer from the local council has crossed the borders of common sense, not because EU officials want to control our crumpets. In fact the Food Standards Agency gives sensible advice to home cooks at village fetes – as the agency does on many other issues.

But after Brexit, we will be able to have our own jam regulation. Indeed, we will have to have our own jam regulation. In practice, of course, the jam regulation the day after Brexit will remain the same as it was the day before Brexit. But – unless and until we negotiate a free trade agreement, neither British nor European customs officials can assure that what is labelled ‘jam’ is – by their own regulations – is indeed jam. And in the absence of fresh agreement on common standards, both British and European jam regulations will evolve over time, largely influenced by the demands of national producers of jam in Britain and continental Europe respectively.

That is the reality of Brexit and trade negotiations: reviewing the rules governing myriads of individual products in mind-numbing detail. Those who thought Brexit meant less regulation, less bureaucracy and fewer civil servants, are in for a surprise.

And so when selling to the EU, British jam makers will adhere to EU standards and when selling to the UK, EU jam makers will adhere to British standards.

This is the same as when British companies trade outside the EU now.

And are all countries not just implementing variations on the Codex Alimentarius anyway?

For example, compare the jam specs in your article with the jam specs in the codex: https://www.google.com/url?q=http://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/ru/%3Flnk%3D1%26url%3Dhttps%25253A%25252F%25252Fworkspace.fao.org%25252Fsites%25252Fcodex%25252FStandards%25252FCODEX%252BSTAN%252B296-2009%25252FCXS_296e.pdf&sa=U&ved=0ahUKEwj4iPi4gPbPAhVLLsAKHbT0ANYQFggEMAA&client=internal-uds-cse&usg=AFQjCNHMI3sV66K2MwU0YvKWPKHL0ks17g

Yes, and every exporter will have to ensure they monitor and comply with two sets of regulations, their home country’s and those in the export market. Double the regulatory burden! Ughh.

Fantastic article!

I tried to make a similar point in a blog post entirely about Directive 2012/28/EU (uses of orphaned works). You’ve made the point much clearer than I ever managed – unified standards make production easier and cheaper. Multiple standards just means more hassle and cost.

Even though not in the EU and without full access to the EEA, Switzerland has adopted a lot of EU regulation. They did this to avoid having production lines because that just pushes up the cost of their exported goods. I suspect the UK will need to do the same, especially for its most successful exports.

I think the idea that markets have rules is something the Leave campaign is yet to understand. Even Car Boot sales have rules.

The Leave Campaign generally is unaware that many EU directives and regulations are simply the conduits down which global regulation comes from

various agencies, such as UNECE, Codex Alimentaries ( WHO), ISO etc – covering such things as motor vehicles, fishery products etc.

For twenty years now the EU has been signed up to adopt global standards where they are agreed. The agreement says “shall” not ” may”. So the EU is very much a law taker, not just a law maker. When I raised this with UKIP a while ago, I got a completely blank response initially. I had taken them to task for bitching at the EU about the labelling requirement for Fairy Liqid to,carry the Hazchem indicator ” eye irritant” ( it is. Just try it!) which came from UNECE in Geneva via the EU in Brussels. Eventually I got the profound statement ” But we’re campaigning against the EU not the UN”. Doh!

Very good.

Just one point – the definition of what is jam is unlikely to be in a trade agreement, but more likely to be in MRA (Mutual Recognition Agreement), which defines common standards, recognises standards and regulatory bodies etc. The food trade regulation (standards etc.) is massive NTB. So most likely EU will have to live w/o those innovative UK jams the government is betting on.

I’ve been screaming on the top of my lungs from June 23 that the tariffs are not the hard stuff – the hard stuff is the NTBs – as anyone who ever tried to import into Japan knows very well.

Standards such as these Jam definitions are not the same thing as regulations. My preferred Jam to buy is not labelled ‘Jam’ at all – it’s called a Conserve, which allows the final product to have more sugar than fruit.

What I don’t want, are artificial preservatives which I expect to be able to read about on the label. This sort of mandatory information is a regulation that I’m glad to have.